Come and See (1985) film review - the most important war film of all time?

★★★★☆

‘Come and See’ is a Soviet war drama that invites us to come and see what war was truly like for the ordinary, the young, and the innocent.

Director: Elem Klimov. Starring: Aleksei Kravchenko, Olga Mironova, Liubomiras Laucevičius, Vladas Bagdonas. 18 cert, 142 min.

‘Come and See’ is a Soviet war drama that depicts the horrors of World War 2 through the eyes of a young Belarusian boy called Flyora. Offering little respite for viewers, director Elem Klimov invites us to come and see what war was truly like for the ordinary, the young, and the innocent. There is perhaps nothing that can prepare you for the onslaught of violence that follows. Set in 1943 in a series of remote Belarusian villages, ‘Come and See’ follows Flyora as he is conscripted by a Partisan Soviet group attempting to resist German invaders. When he captures the attention of an enemy plane, Flyora is unwittingly thrust headlong into a battle for survival that will test the minds of even the most seasoned of filmgoers.

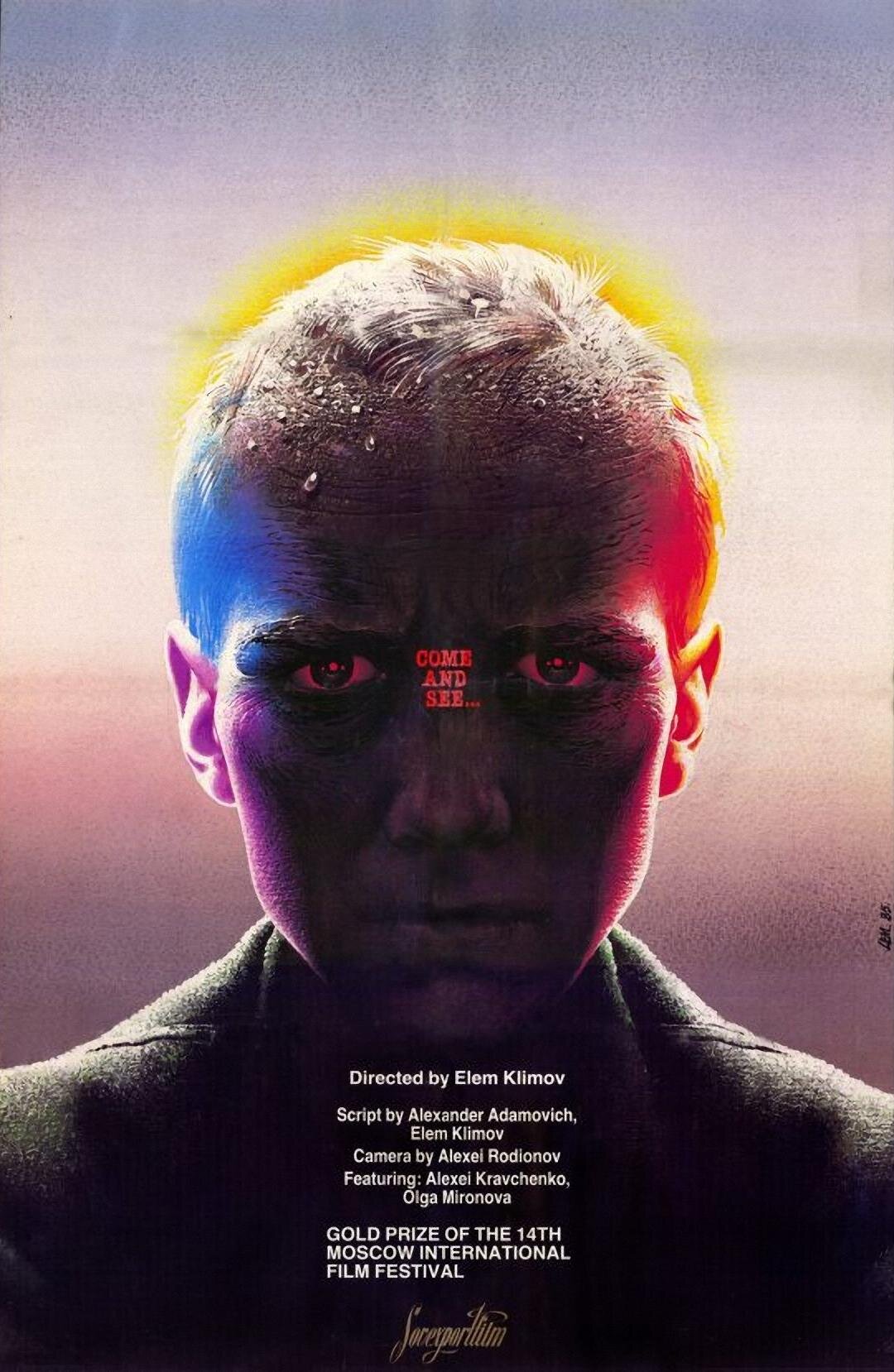

‘Come and See’ (1985) film poster artwork

The reality and authenticity of ‘Come and See’

Dubbed by many to be the best and most important war film of all time, Klimov’s work is based on his own experiences fighting as a Partisan in a German-occupied Belarus. Noting a significant lack of coverage on the extensive horrors experienced by the Belarusian people during World War 2, Klimov vowed to provide some kind of justice:

“I understood that it would be a very cruel film and hardly anyone would be able to watch it. I told about this to the co-author of the script - Belarusian writer Ales Adamovich. But he replied: “Let them not look. We must leave this behind. As evidence of war, as a plea for peace.”

Having started filming in 1977, Klimov fought against the Soviet State Film Agency’s enforced censorship vehemently for 8 years until his film was finally allowed to be released. This is testament to its shocking subject matter, and is I believe important to note when viewing the film itself. The desperation to relay the kind of anti-war message that ‘Come and See’ provides with every shot, camera angle, and close-up, is further testament to its importance as a documentation of the sheer brutality of war. Klimov’s cinematographically stunning account of the victims of war is disturbing, upsetting, but ultimately paramount to ensuring that history does not repeat itself.

A film that is genuinely difficult to watch

As visually stunning as it is horrific, it is undoubtedly the terrifying reality of ‘Come and See’ that makes it all the more astounding to watch. Aleksei Kravchenko delivers a particularly harrowing performance as young Flyora. From experiencing the death of his family to the razing of entire villages by German troops, Kravchenko’s convincing portrayal of a boy with nothing left to lose is genuinely difficult to watch. Visibly aged beyond his years by the film’s end, the artful execution of Flyora’s character prevents ‘Come and See’ from appearing self-indulgent; and instead makes it an intricate character study representative of the experiences of real Belarusian people.

Warning: contains spoilers. For me, the most intriguing aspect of 'Come and See’ is Klimov’s integration of surrealist techniques into the film’s breathtaking climax. Having witnessed the harrowing burning of a barn filled with Belarusian villagers, Flyora stumbles away and observes as the Partisans capture and kill a group of German collaborators. At a local level, the fight may be over; but what does he have to show for it? The young boy has clearly been driven mad, and Klimov demonstrates this in a slightly clichéd but nonetheless powerful manner.

The ending of ‘Come and See’ explained

Walking away from the culmination of death and destruction, Flyora comes across a framed portrait of Adolf Hitler. In what is perhaps a homage to the film’s pre-censorship title ‘Kill Hitler,’ we see Flyora repeatedly shoot the portrait. As he does so, a montage of real footage plays intermittently, displaying Hitler’s life in reverse. With Mozart’s ‘Lacrimosa’ playing in the background, the sheer passion of the young boy is astounding. With this, Klimov grants us a glimpse into the unadulterated pain and anger of war’s survivors. However, seeing Hitler as a baby, Flyora is unable to shoot. He stops shooting and breaks down in tears. Thus, Klimov poses a question to the audience:

Given the chance, would you shoot an infantile Hitler?

As trite as it seems, ‘Come and See’ manages to pose such a question in a way that is as gritty and compelling as the film’s entirety. Klimov forces his audience to commit to a level of introspection that is uncommon for a war movie, inducing an awareness of our own humanity that persists long after the credits have rolled.

Should you watch this before you die?

Overall, ‘Come and See’ is a chilling, distressing, and extraordinary depiction of World War 2 that is unsullied by romanticism and unmollified to the extreme. As controversial as it is influential, I would agree that it may be one of the most important war films of all time, if only because of its unusual filming process and shocking realism. I would urge others to watch it simply because with such an ending, ‘Come and See’ is guaranteed to leave its mark; whether you like it or not.